Mended by the Muse: Creative Transformations of Trauma

Interview by Maria Tammone

Maria Tammone: Below you will see some phrases that I found in your book: “The creative process can be immensely reparative…” and “the creative action is one of the most effective ways of coping with trauma and its aftereffects…” This is the core of your work. Although I realize that the subject is enormous and complex, I wonder if you could illustrate some essential points of your thoughts about this.

Sophia Richman: Trauma results in a profound sense of chaos. Creating art, in its different forms, holds the possibility of organizing one’s internal experience, making sense of it, finding meaning in it. In the book I give many examples of survivors who after their ordeal had a powerful need to express what they had been through. In the process of writing their memoir they could turn a situation where they had been rendered helpless into one where they had control. Also trauma tends to isolate the victim from others and through the creative process one is able to bear witness as well as find witnesses in others providing an opportunity to reconnect. For instance Primo Levi’s biographer Ian Thomson writes that upon his return, Levi’s need to express himself was so intense that he talked to anyone who was willing to listen, to strangers on the street, on trains, and buses about what had happened to him in Auschwitz. His memoir, which he wrote in just 10 months from notes on scraps of paper, back of train tickets, and flattened cigarette packets, represented what Levi called “an interior liberation.” Thomson described how the words poured out of him ceaselessly as if he was in a trance-like state.

Sophia Richman: Trauma results in a profound sense of chaos. Creating art, in its different forms, holds the possibility of organizing one’s internal experience, making sense of it, finding meaning in it. In the book I give many examples of survivors who after their ordeal had a powerful need to express what they had been through. In the process of writing their memoir they could turn a situation where they had been rendered helpless into one where they had control. Also trauma tends to isolate the victim from others and through the creative process one is able to bear witness as well as find witnesses in others providing an opportunity to reconnect. For instance Primo Levi’s biographer Ian Thomson writes that upon his return, Levi’s need to express himself was so intense that he talked to anyone who was willing to listen, to strangers on the street, on trains, and buses about what had happened to him in Auschwitz. His memoir, which he wrote in just 10 months from notes on scraps of paper, back of train tickets, and flattened cigarette packets, represented what Levi called “an interior liberation.” Thomson described how the words poured out of him ceaselessly as if he was in a trance-like state.

Emerging from your experience through painting and in becoming a psychoanalyst (in which the “spoken word” is the main way of expressing oneself.) What led you to become a psychoanalyst?

No doubt my choice of psychoanalysis as a profession was multiply determined, but I believe that my early trauma history was an important factor in that choice. In the book, I point out that early experiences, particularly troublesome ones, function as a powerful inner force that draws us like a magnet to situation and events that provide an opportunity to work through and hopefully to come to terms with what we had to passively endure when we had no control. Trauma cries out for expression selectively influencing our perception and determining our interests and preoccupations. This is part of a healing process that goes on in myriad conscious and unconscious ways throughout our lives.

Susan Erony, Self-Portrait, (2000). Oil on canvas, 24 x 18 inches. Collection Cape Ann Museum, Photo credit: Cape Ann Museu

For me psychoanalysis as a choice of profession makes great psychological sense and this is probably why I find it is so fulfilling. My early trauma history of living in hiding during the Nazi occupation of Poland has found its way into a profession that creates the opportunity for both its reenactment and its repair. As a toddler and young child I lived under the constant threat of death that was communicated to me by my terrified parents, not by words but by their strange behavior. My mother, who passed as a Catholic, smiled and was friendly to outsiders, but she could abruptly shift into a state of terror once inside of our apartment. Hidden in our attic was my father who had escaped from a concentration camp. At the age of 3, it was impressed upon me, that his presence was a secret to be kept from the outside world. My need to be on my guard constantly and to make sense of behavior that defied understanding was pervasive and profound.

Eventually, through my own analysis and through the writing process, I came to see how some aspects of these early themes found their way into my adult choices. Psychoanalysts are the keepers of secrets. Psychoanalysts choose their words very carefully; they tend to speak little and listen intently for what is said and what is not said. Psychoanalysts are attuned to the nonverbal and psychoanalysts are constantly struggling to understand what is going on. All states which I am intimately familiar with. My profession gives me an opportunity to face what was once thrust upon me and unbearable, but this time from a position of choice and strength. Helping others to face what has been hidden in their lives resonates with my own struggle and gives me a sense of connection and meaning.

Your personal experience as a” hidden child” during the war was the creativity which saved you. Would you like to share with us in what way the idea of painting emerged as a form of your personal “safe” world?

One of the few avenues to self-expression during my years in hiding was drawing. There were no toys, there was no money to buy them, but paper and pencils were usually around. I drew pictures on the back of envelopes, on lists, on old calendars, any discarded pieces of paper I could find. My mother encouraged it; she admired my drawings and occasionally would engage me in a drawing game, something akin to Winnicott’s Squiggle game. One of us would draw something, the other had to guess what it was, and make her version of it or elaborate on it. It was one of the few activities that we could do together, and it was safe. It was also something that I could do alone since my mother kept me home and away from other children, probably because there would be less chance of inadvertently betraying my father’s presence.

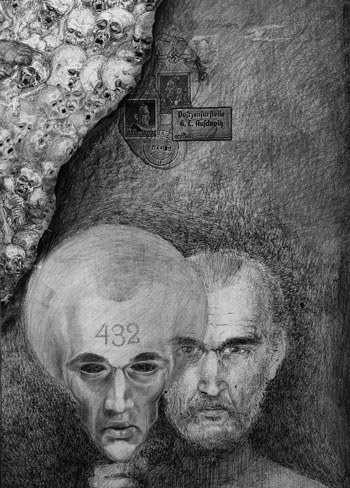

Marian Kolodziej, Double Self-Portrait. Drawing: pen and ink on paper. Photo: Jason Al Schmidt & Christof Wolf, S.J, as seen in the documentary, the Labyrinth.

I find very interesting and “creative” your perspective about creativity as “a potential that exists in all of us to some degree” and “changes or influences an existing situation.” Can you tell us more?

In this book I use the concept of creativity broadly. I am not limiting it to the expression of a special artistic talent or to the creation of a unique and novel product of lasting value for society. I am not addressing the talented and famous, although some of the people I write about are in fact very talented and well known. I also use the term “artist” loosely, referring to the individual engaged in the process of making art, without judgment regarding the quality of the product. Engagement in the process of making art can be gratifying and reparative regardless of level of ability. My emphasis here is on creativity as a potential that exists in all of us to some degree – the ability to find unique ways to express ourselves and to solve the problems that we face by shifting our perspective. Everyday creativity refers to a problem solving ability associated with flexibility of thought and lack of what we used to call “functional fixedness” that allows people to improvise, to be open, curious, and tolerant of ambiguity and unpredictability. Attempts to master traumatic circumstances and to cope with their aftermath can be ingenious and inspired; desperate times often lead to heightened creativity and innovation as the proverb “necessity is the mother of invention” reminds us. Creativity under those circumstances is associated with flexible adaptation to changing circumstances and is part of a survival capability (Richards, 2007).

Regarding the title. “Mended by the Muse” How did you come about this title and can you tell us a little more about the significance?

A writer once told me that to sell a book you need a great title, so I spent many months obsessing about titles and trying them out on Spyros – poor man! I knew that I wanted to use the Muse metaphor in the title since it communicated my essential ideas about witnessing. As I conceptualize it, the Muse is a relational presence in what would otherwise be a solitary activity of making art. It is a dissociated self-state; an embodied image of an “other” who serves an inspiring, mirroring, and witnessing function for the artist. Like an imaginary friend, the Muse exists in the intermediate area of experience – the potential space between psychic reality and the outside world (Winnicott, 1967). The other concept, which I wanted to include in the title, was the healing function of creativity. Eventually I came up with the idea of “Rescued by the Muse.” When I ran that title by Donnel Stern, the series editor and my friend, who incidentally loves playing with titles as much as I do, he suggested the word “Mended” instead of “Rescued.” And so I had my perfect title. Mended was a much better choice; besides the fact that it has a melodic sound when paired with the word muse, more importantly, its connotations are in keeping with my ideas about the recovery process. Although I speak of healing in the book, I am aware of the limitations of the idea that it is possible to fully heal from catastrophic trauma. In many cases, it is questionable that psychic pain can ultimately be “healed.” In my view, healing is more of a goal to be approximated than a result reached. Intense suffering can be lessened with time, with therapy, or with artistic expression – but scars do remain even after wounds have healed, and the pain of past losses can be triggered by current events. Mending, to me, suggests that a tear has been repaired, but the damage can still be observed if one looks closely.

A writer once told me that to sell a book you need a great title, so I spent many months obsessing about titles and trying them out on Spyros – poor man! I knew that I wanted to use the Muse metaphor in the title since it communicated my essential ideas about witnessing. As I conceptualize it, the Muse is a relational presence in what would otherwise be a solitary activity of making art. It is a dissociated self-state; an embodied image of an “other” who serves an inspiring, mirroring, and witnessing function for the artist. Like an imaginary friend, the Muse exists in the intermediate area of experience – the potential space between psychic reality and the outside world (Winnicott, 1967). The other concept, which I wanted to include in the title, was the healing function of creativity. Eventually I came up with the idea of “Rescued by the Muse.” When I ran that title by Donnel Stern, the series editor and my friend, who incidentally loves playing with titles as much as I do, he suggested the word “Mended” instead of “Rescued.” And so I had my perfect title. Mended was a much better choice; besides the fact that it has a melodic sound when paired with the word muse, more importantly, its connotations are in keeping with my ideas about the recovery process. Although I speak of healing in the book, I am aware of the limitations of the idea that it is possible to fully heal from catastrophic trauma. In many cases, it is questionable that psychic pain can ultimately be “healed.” In my view, healing is more of a goal to be approximated than a result reached. Intense suffering can be lessened with time, with therapy, or with artistic expression – but scars do remain even after wounds have healed, and the pain of past losses can be triggered by current events. Mending, to me, suggests that a tear has been repaired, but the damage can still be observed if one looks closely.

What can you add regarding the role of dissociation in the creative process?

One of my goals in this book has been to introduce a relationally informed theory of the creative process. I have taken relational concepts of dissociation and witnessing and extended them to the artistic realm, an area that has been relatively neglected by relational thinkers. Previously, a couple of theorists had identified dissociation as a predominant feature in the creative process but these formulations remained within the drive theory model.

One of my goals in this book has been to introduce a relationally informed theory of the creative process. I have taken relational concepts of dissociation and witnessing and extended them to the artistic realm, an area that has been relatively neglected by relational thinkers. Previously, a couple of theorists had identified dissociation as a predominant feature in the creative process but these formulations remained within the drive theory model.

In my interviews with artists and from personal experience with writing and painting, I have noted that when engaging in the artistic process one enters a state that has been referred to alternately as surrender, trance, or flow (Csikszentmihalyi (1990), all aspects of dissociation. This altered state is characterized by a high level of absorption, intense focal concentration, a loss of awareness of one’s surroundings, time distortion, and a suspension of reality constraints. In that state one is able to temporarily put aside evaluative judgment and allow emotionality and imagination to hold sway. When the artist is in the inspirational phase of the creative process, she enters a dissociative state in which she experiences more vivid imagery, a lessening of anxiety and tension, and a greater receptivity to new ideas.

During the creative process, when the individual surrenders to the experience, there is a temporary dissolution of self-boundaries and a greater psychic fluidity between self-states. It is my contention that the normal need for the unity of self is set aside during states of altered consciousness allowing for greater access to a range of self-states, to more fluid communication between them, and a greater freedom to explore the different voices coming from within. The suspension of boundaries between self and not-self and between the inside and the outside world not only facilitates shifts in self-states but also the possibility of regression into more primitive emotional states and progression into future fantasy.

Regarding “Witnessing”. You mention the perspective of Donnel Stern about the function of “witnessing” and the need for witness, especially for the trauma survivors. Can you give us your deeper thoughts on the witnessing function of art?

Art serves the witnessing function on multiple levels including bearing witness (to self and to cultural tragedy) and being witnessed by others; I believe that both of these aspects of witnessing – bearing witness and being witnessed – are essential to the healing process. Memories of trauma are often unmentalized and cannot be contextualized in the present. Art can stimulate and assimilate potentially dangerous degrees of affect, thereby extending the limits of what is bearable, allowing progressive integration within the safe holding presence of aesthetic structure. By expressing the internal pain, the artist externalizes it, organizes the chaotic experience, fashions a container for it, and invites others to become witnesses to his suffering. Trauma often ruptures ties with others and leads to a sense of isolation. By eliciting the witnessing of others in their role as audience or readers, the trauma survivor lets others into his world in his own terms and from a safe distance. Being known and recognized and appreciated can be a source of self-esteem, a quality in short supply in the life of a trauma victim. Finally, when the artist’s work memorializes a catastrophic tragedy, he also bears witness to the trauma that has taken place. For countless survivors of genocide this is one of the powerful motivating forces for giving testimony and creating artistic products such as memoir, sculpture, and other forms of memorializing art.

One of my favorite examples from the book is the story of Vedran Smailovic, the ‘cellist of Sarajevo,’ who during the Bosnian war daily played his cello in the center of town while bombs went off around him. Through his cello (his weapon as he called it) he found a way to express his anger and his sorrow about the tragedy that was taking place. His was an anti-war statement and a memorial to those who had been killed; it was a creative act that stood in direct opposition to the destruction around him.

Can you tell us more regarding the creativity and art in the context of life-threatening illness and aging?

The notion of a last chance to fulfill what has been set aside before it’s too late is a powerful theme in the life of those who are confronting their mortality, either as a result of life-threatening illness or of aging or both. In illness or in old age, existential concerns such as death, isolation, and meaninglessness, take center stage. Both physical illness, and the gradual deterioration of the body associated with aging, can be seen as potentially traumatic events – with an attendant sense of irreparable loss, helplessness, and disturbance of self-image and identity. Old age is a time of decline and a time of endings. The body shows signs of deterioration, losses accrue, contemporaries die, and memories begin to fade. With retirement, there is more time to contemplate one’s life and the inevitability of death. Simonton (1989) has noted that creativity tends to undergo resurgence in the later years of life; a pattern that he believes is related to the contemplation of death. Stage theorists, Jung and Erikson wrote about this stage of life as presenting specific challenges as well as opportunities for growth and renewal. Knowing that one will cease to be, stirs a desire for generativity; a way to leave a mark on the world – a sign of one’s existence. The tasks at this stage of life include life review and retrospective evaluation; the maintenance of a sense of continuity over the life span; an acceptance of limitations; and a creative adaptation that holds some possibility of transcendence as well as the potential for fulfillment of interrupted or submerged aspects of self.

In this last chapter entitled “Confrontation with Mortality” there is a brief section on data from neuroscience about the effects of aging on the brain. We know that diseases such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s selectively affect different parts of the brain and that the parts involved in creativity can remain relatively intact for a long time. Case examples of severe illness and aging including a clinical one from my practice illustrate how art can facilitate the working through process of major losses and help to restore a sense of control and connection with others.

In your book there is a chapter dedicated to music as a form of therapy. In our IARPP community, as you know, one of our colleagues uses music and “opera” to represent and share psychoanalytical themes. What do you think about the similarities and differences among these different forms of art (painting but also writing for you) in your works?

Actually I am familiar with several psychoanalysts in our IARPP community who are interested in the interface between music and psychoanalysis in addition to Gianni Nebbiosi whom I assume you are referring to. Frank Lachmann has written about this subject as has Stefanie Glennon, Steven Knoblauch, and Malcom Slavin, and of course Spyros D. Orfanos, my favorite who wrote the chapter in this book “Music and the Great Wound” which you refer to.

As to your important question about the similarities and differences among the different art forms, it is an area I have given a lot of thought to, particularly as it relates to my own experience with painting and writing. Although I find the creative process similar in both modalities with regard to the dissociative aspect which I referred to earlier in this interview, the function which each of these art forms has served for me is quite different. It is through writing that I am able to best express my sorrow and to organize my experience, searching for just the right words to capture my complicated emotions and complex ideas. This is where I struggle to make sense of my feelings and of my personal history. In contrast, painting is primarily an aesthetic activity that has a powerfully soothing effect on me even as I struggle with the challenge of mastering the task I am engaged in. I am guided by a powerful desire to create a product that matches my internal experience or perception of a landscape or a still life that I find interesting or beautiful or meaningful. In both modalities, writing and painting, when I have met the challenge, I know it deep inside, and have a sense of completion and wholeness as well as a sense of fulfillment.

All forms of art impose a certain form upon unruly or chaotic feelings and all forms of art pose a challenge to master and organize complex feelings and ideas so that the external product captures the internal experience. Daniel Stern (2010) distinguishes between various arts in terms of the forms of vitality that they elicit. According to Stern it is the “time-based” arts such as music, dance, theater and cinema that are most relevant in giving rise to the experience of vitality. Among the arts, music has a strong and basic connection with the emotions; it is first experienced in the womb when the fetus is exposed to maternal sounds. My husband Spyros writes that music is often what affects and emotional experiences feel like. Music possesses unique properties in its potential to evoke and convey a range of affects connected with grief and consequently plays a special role in mourning serving the mourning process for composer, performer and listener as well.

What next? Do you have any new books or projects planned in the future?

As gratifying as this experience of writing has been for me, I am ready to take a break from it. When I was writing my book, I had to give up painting and at this point I am eager to return to it.